|

Shadowboxing — Русский репортер №25 (55) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 2024 November 23 | ||

| Current Mood: | pondering | |

| Now Playing: | "Passing Through All Happy Dreams Like Hallways" by Bug Bus Piano | |

|

||

Originally posted semi-anonymously on cohost.org on June 7th, 2023.

It's a translation of an article from 2008 about St. Petersburg antifa. It's a pretty rough longread with a bunch of content warnings, some pretty controversial statements, written with smugness and condescension, but still providing an interesting insight into the state of resistance to neo-nazi movements in late 00s Russia. Huge thanks to ray for helping me with the translation, and also to Nathalie for providing consultation on a couple of difficult language moments.

Content warnings: racism, xenophobia, homophobia, violence, police violence, nazi violence, murder, hate speech, casual use of ableist language

Anna Rudnitskaya

July 3rd 2008, 00:00

Original article (official archive): https:// expert.ru /russian_reporter/2008/25/antifashizm/

Original article (alternative archive): https:// antifa.fm /article/2009/04/shadow-fight-1 ; https:// antifa.fm /article/2009/04/shadow-fight-2

Translator's note: this article translation was motivated by the desire to share a small part of the modern Russian antifascist movement history. Despite presenting the author's very subjective perspective on the topic, I believe that the article still contains valuable insight into the time period and the people involved.

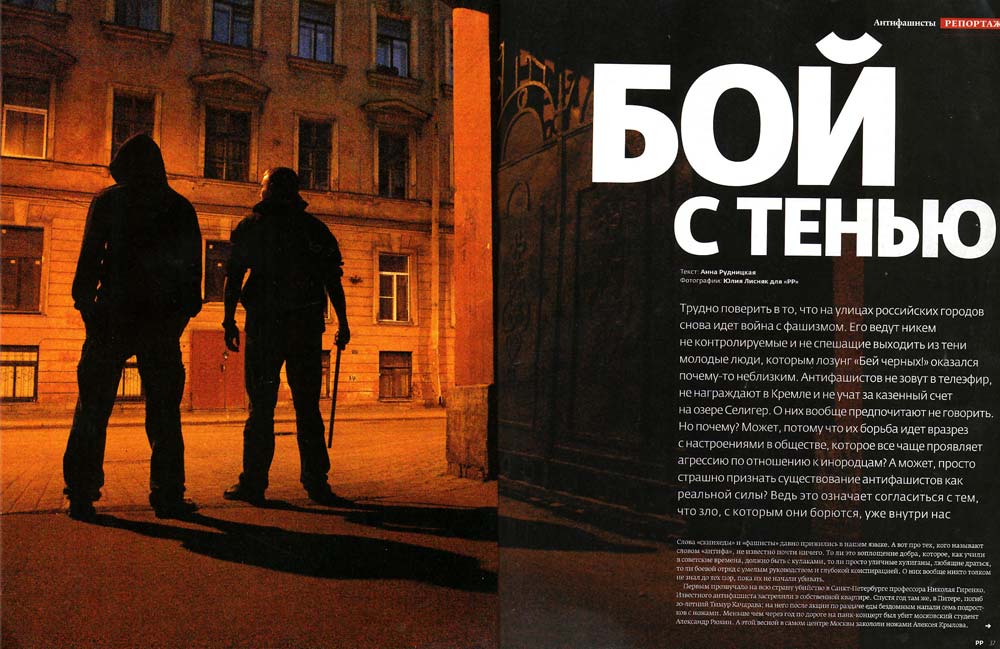

It's hard to believe that a war on fascism is taking place in the streets of Russian cities once again. It's being led by the uncontrolled, reluctant to come out of the shadows young people, who, for some reason, couldn't relate to the slogan "Punch blacks!". Antifascists are not invited on TV shows, are not awarded in Kremlin, and are not trained with the government money at Lake Seliger. It's generally preferred not to talk about them at all. But why? Could it be because their fight goes against the public sentiment, which has recently been showing more aggression towards foreigners? Or maybe it's just fear of acknowledging the existence of antifascists as a real force? After all, that would mean agreeing that the evil they are fighting with is already inside us.

The words "skinheads" and "fascists" took root in our language a long time ago. However, there's barely any knowledge about those being called "antifa". They might be the embodiment of good that, as it's been taught in the Soviet times, must be willing to punch, or mere street hooligans who love to fight, or a combat squad with capable leadership and deep cover-up. Nobody knew anything about them until they started getting killed.

The murder of Professor Nikolay Girenko in Saint Petersburg was the first to echo throughout the country: the well-known antifascist was shot in his own apartment. One year later, once again in St. Petersburg, at the age of 20 died Timur Kacharava: he was attacked by seven teenagers armed with knives after a gathering to share meals with homeless people. Less than a year after that, a Moscow student Alexander Ryuhin was murdered on his way to a punk concert. And then this spring, in the very heart of Moscow, Alexei Krylov was stabbed.

Rash

Everyone in St. Petersburg I talked to about antifascists would sooner or later mention the name "Rash" — and nothing else: "If he wants to — he'll tell you himself". I only learned that his real name was Oleg Smirnov; that in May he was prosecuted for organising a mass brawl (around 30 antifascists against half a hundred DPNI [translator's note: Movement Against Illegal Immigration] rally participants two years ago in autumn); and that among the St. Petersburg antifascists he was an iconic, if I may say so, figure: 16-year-old teenagers and 30-year-old women would talk about him with equal respect.

Everything else he, indeed, told me himself.

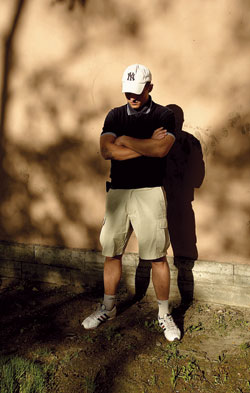

Rash is 22. He got kicked out from the Faculty of Sociology of Saint Petersburg State Institute of Culture — according to his own confession, for slacking; he works at a company specializing in landscape design, as a workman; plays in a hardcore band Crowd Control; and in St. Petersburg he was the one to start what is commonly defined by the word "antifa".

For Rash himself everything started even earlier. At 14 he was a punk, and would often get beaten by skinheads in the streets — back then, he says, it was the darkest time for punks in that regard. He started wondering if there was a force that could deal with "skins" — like antifascists — but couldn't find anyone except for the communists represented by Federation of Socialist Youth and, later, anarchists. From anarchists he managed to learn about an organization that had been recently formed in St. Petersburg, "Punk-vozrozhdenie" [translator's note: "Punk-revival"] — a punk community for self-defence against the skins. Its members were security guards at concerts.

A couple years later the community died out, but punks and skins remained. Oleg then decided to take initiative, and with his friends he created the first "affinity group", which is translated from English as "a group of like-minded people", but in Russian Criminal Code is more often interpreted as "a gang". Basically, an antifascist combat squad — a thing that journalists describe with the word "antifa". Now there are several such groups in St. Petersburg already, with at least one hundred members overall, and not all of them are even aware of each others' existence. But that first group hit the streets of St. Petersburg at the end of 2003.

"We decided to patrol the area near metro station "Prospekt Bolshevikov", where a dormitory for foreign students, who would often get assaulted, was located. We would walk around for 3 hours, freezing like idiots — not a single nazi. One day we decided to ask the guys in the dormitory where the nazis were usually hanging out. Sent one of ours there. Students got scared, started pointing at us through the window: "There they are". They didn't really see the difference between normal skinheads, like us, and bons... [translator's note: short for boneheads]"

By "normal skinheads" Rash means skinhead-antifascists like himself. Actually, his nickname is the name of one such skinhead group, "rashes" — derived from Red and Anarchist Skin Heads (R.A.S.H), or "red skinheads". There are also "sharps" — from Skin Heads Against Racial Prejudices (S.H.A.R.P.). And "boneheads" (meaning "empty headed" in English) are nazi-skins. European skinheads came up with this differentiation in the previous century as an answer to the emergence of far-right members in their traditionally leftist environment. Russian "true" skinheads also refer to boneheads, or "bons", as "bald", often following this adjective with the noun "beasts".

What is happening between fascists and antifascists, and do the murders of the latter (Timur Kacharava in St. Petersburg, Alexander Ryuhin and Alexei Krylov in Moscow) mean a real war of annihilation? And in general, being an antifascist in Russia — is it simply dangerous or mortally dangerous? The general consensus from my conversations with the St. Petersburg antifa concludes: it is very dangerous, it can be mortally dangerous, but also the nazi forces are not as great as it may appear from reading their forums or listening to their leaders' speeches.

"I don't consider every random drunkard in a bomber and suspenders a fascist," Rash says. "We have several hundreds of serious enemies in St. Petersburg. Of course, there are thugs like Mad Crowd — a nazi gang slaughtering children on condo staircases. But I think they are harming their own, because murdering a child is something that can't be justified at all, you can't earn any glory with this. Those are, fortunately, few. In general, bons are not particularly good fighters with not much of organization. There's simply a lot of them, more than us, and their numbers keep growing, and they are getting better prepared. But still, in general, they are cowardly, and prefer to run as soon as they are attacked. They fear us more than we fear them, because we understand well who we are dealing with."

Regarding "we do not fear" — there's some exaggeration to that. Rash was the only one among the antifa I talked to who gave a permission to use his real name in the article and even agreed to take a photo, though with his face covered. The others flatly refused. And even Rash agreed in an "I don't care anymore" way. His photos are on nazi websites, and recently his current apartment address got posted there as well. Rash always carries a knife on him, which he has an official bearing license for. He has been assaulted twice — those were the two cases when he had to be seen by a doctor, as he doesn't consider a concussion a reason enough to go to a hospital anymore. These last few years when his mother calls him she asks: "Are you still alive?" instead of "How are you?"

"And what does your mother think about this activity of yours?"

"Well, what does she think?.. She says she's against violence. Well, I'm also against it. But Hitler himself said that if communists gave a pushback to fascists in the streets early on — there wouldn't be the Second World War."

Younger comrades

We agreed to meet near metro station "Gostiny Dvor". They have already been waiting — three guys around 17-18 years old, two in baseball hats pulled down, the third — bareheaded, smiling.

"Pyotr," one of the two in hats introduced himself.

"Pyotr," the second one informed.

"I see," I turned to the third, smiling one, "You're Pyotr, too?"

"Pyotr is fine," he answered. "But usually they call me Homer Simpson."

One of the two Pyotrs clarified that if I'm interested in a surname, I can write down Kropotkin. For those who don't remember, that's the name of one famous anarchist theorist.

At the table of the closest street cafe two Pyotrs and one Homer describe how one becomes an antifascist. The three of them represent almost the entire set of "places" where people who join antifa come from: aside from the corresponding beliefs in their pure form, it's politics and music. After all, street antifascism is not only an ideology, but also to some extent a youth subculture, or more precisely, a mix of several: skinheads (the "true" ones), punks, and hardcore music fans. Dr. Martens boots and the skill of rolling pants up correctly are not any less valuable in the company of two Pyotrs and one Homer than the ability to refute arguments of DPNI supporters. That's why those who imagine proper boys from nice Jewish families upon hearing the word "antifascist" are not entirely right.

Homer Simpson was both a skateboarder and a punk. And an antifascist — "always", he says. His father is a war historian, taught him about the war [translator's note: World War II].

"And when at 17 I learned that there are guys like that," Homer explains, "I decided: enough, I've had enough!"

"Enough of what?"

"Well, I would get beaten, humiliated — I had long hair, piercing, a skateboard. Was bullied not from a gopnik angle, but specifically a nazi angle. They'd say: "You live in Russia — respect Russian culture". But respecting Russian culture — is that wearing valenki and playing balalaika? On the contrary, subcultures are a sign of progress in a society, there are no punks or skaters in Third World countries. For example, are there any subculture folks in Zimbabwe?"

"They are everywhere..." snickers, lightening up, Pyotr (the Kropotkin one).

He, with his shaved head under a baseball cap, once again started explaining to me the difference between "true skinheads" and boneheads:

"They simply stole everything from us — the appearance, the clothing style. So now everyone thinks: if your head is shaved — you are a fascist. But the real skinheads — you know about them, right? They were ordinary white guys who worked at factories in England alongside the workers from Jamaica, and nobody gave a shit about nationality. It was a labor movement, a class one — simply anarchists like that. Absolute internationalists."

"Even now it so happens that a bonehead starts realising that true skinheads are something entirely different, and joins antifa," Homer adds.

"Really?! And you know someone like that, someone reformed?"

Pyotr Kropotkin giggles shyly, Homer shoves his elbow into Pyotr's side.

"Here he is, in front of you."

It turns out that Pyotr "started" as the most ordinary Russian skinhead, in other words not an antifascist at all. It all took place in the Nevsky district of St. Petersburg, where he grew up. ("The vilest hotbed for this type of shit," Homer rates his friend's homeland.)

"It's just, it was a trend back then," Pyotr shrugs. "I wanted to realise myself somehow, to feel strong. Back then it seemed like being a nazi was cool... But we didn't do any serious stuff. We beat up punks, but without knives, nothing extreme. And then I understood that it's total bullshit — this ideology."

"Understood? How so?"

"Well, gradually. But when I saw the news about Timur Kacharava I woke up completely. I thought: what's going on?! I didn't mean to kill people. I'm actually a peaceful person — an anarchist."

As a kid, this peaceful person wanted to become an astronaut, as a result he studies at the institute to become a specialist in radio electronics. And Homer studies... to become a cook.

"Just felt like it — that's all," he happily explains. "I don't think it will be my main profession, I will probably keep deciding and rediscovering myself throughout my whole life. I reject any politics, just want to grow up, have a family, raise kids, and not burden anyone."

What Pyotr Kropotkin and Homer Simpson have in common, and why they both call themselves antifa is, by and large, unclear.

"You know, anarchists have a motto: "Everyone is different, but all are equal"," Pyotr says. "So what if we have different political views? ("I don't have any political views at all," Homer specifies.) We don't talk about politics when we meet."

"But what is the antifa's goal, in general? For example, what's your and Homer's common goal? To defeat fascism?"

"Fascism can't be defeated at all," the other Pyotr calmly says, after being quiet the entire conversation. "The goal is to stop racist violence in the streets, and we are succeeding at this. If previously nazis used to feel confident in the city and walked around all dressed up for a fight — now it's not like that."

Back then, more specifically just four-five years ago, the guys tell me, boneheads were "pressuring everyone". People with shaved heads and rolled up pants could be found on Nevsky Prospekt. Skateboarders and rappers would often hang out near metro station "Moskovskaya", and nazi raids were frequent there.

"And subculture folks simply got fed up. So they resolved to respond with violence," Pyotr continues. "And now nazis are already scared to express their views."

"Scared of you or the police?

"Partly the police — lately cops stopped being all affectionate with them. But scared of us as well."

Pyotr-not-Kropotkin doesn't listen to punk music and is indifferent to anarchist ideas. How did he, of all people, turn up among antifascists?

"We were taught this at school," he replies.

"At school?!"

"Well, yeah. We had these tolerance trainings, and there I realised that fascism needs to be confronted somehow. I started with reading all the websites on the Internet, then I wrote on a forum that I wanted to join antifa, and asked to be introduced to someone. So they introduced me."

Opponent

The tolerance trainings Pyotr II was talking about are held in several St. Petersburg schools (where it's allowed) by a history and law teacher, as well as one of the local department leaders of a youth movement "Oborona" [translator's note: "Defence"], Maxim Ivantsov.

After hearing my description of Pyotr, he quickly understood who I was talking about:

"It's bugging me. His parents, naturally, have no idea what he does. And it's not like I can stay silent, but I don't have the right to tell them either."

The trainings created by Maxim, which also cause the conflict between his civil and pedagogical stances, work the following way. After various exercises to get to know each other, it comes to the crux of the matter — in a play-based way, says Maxim. Like this, for example: "Is it better to be a gay or a fascist?". This is a question high schoolers are invited to answer during one of the exercises. A line is drawn, with "gays" standing on the one side, and "fascists" on the other. Initially, Maxim says, the entire class is crowding on the "fascist" side. Then the discussion begins. Last time 13 out of 14 people became "gays" by the end of it.

"Usually it's worse," Maxim adds, "and they split roughly in half. Even then, the reason for that might just be that recently the general attitude towards gay people got more tolerant. And still, one half remains on the "fascist" side."

Maxim is under 30, he wears jeans and doesn't really look like a school teacher. Perhaps, that's why he is able to find a common language with teenagers.

"I try to influence them through experiences, including personal ones. I am from Estonia myself, so I tell them how I was treated in Estonia for being Russian. Or that I have a fear of Roma people, but can still understand that it's about me and not Roma people: it's me being afraid of them, which is not their fault. Trainings like these are, actually, quite a dangerous thing: if you don't master them, you are more likely to achieve the opposite result. That's why no handed down "tolerance" programs ever work. Especially in the climate where neither the State, nor the schools are tolerant. A teacher who doesn't respect her own students can't nurture tolerance to other people in them."

"And what's your opinion on street violence, including that from the antifascist side?"

"Negative," Maxim replies. "Negative. But we — those who stand for non-violent forms of resistance — understand that we are beginning to lose to the supporters of violent methods. Because people join antifa not only out of desire to do something kind and helpful, but also for the rush of energy that one can only get in the streets. It is especially noticeable nowadays, when all the "youth movements", including both fascists and antifascists, suddenly got younger. That's why the levels of violence got higher, since there are absolutely reckless people on both sides. After all, when a person gets older they acquire certain values. If previously the average age of any subculture member, including skinheads, was 20 years, now every high schooler is already in on this."

"What are the reasons for this?"

"The Internet. Previously, social life of some sort would normally begin at the institute — new social circles would form, new acquaintances. But now everything is on the web: all the videos of nazi assaults, all the fights that antifascists get involved in. And any student has access to the Internet... Just a few years ago this stuff was almost unknown among high schoolers, now everybody knows. Mostly about fascists. Less so about antifascists: mainly that they are freaks who beat up bons who want the best for Russia."

"And why exactly is it bad to fight nazis by their own methods?"

"Because you can't defeat violence with violence. You can't make the world more tolerant with fists. And most importantly, those who take part in this don't notice how they become more aggressive. At first you are an antifascist, next you are a football hooligan, and then you already fight not for a just cause, but simply because you enjoy fighting."

"What about Pyotr? Does he fight for a just cause?"

"Pyotr... I'm afraid that recently he's been more into fighting for the sake of it."

Elder Comrades

Not everyone among antifascists, even those of them who don't participate in the attacks on nazis, shares Maxim Ivantsov's perspective.

Katya teaches English at a university. She's between 30 and 40, fragile figure, daydreaming eyes. She doesn't fight with bons, but participates in other antifascist street protests, including unauthorized picket lines and rallies. Therefore, she still needs to be prepared for a fight — if not with nationalists, then with policemen.

Last year in November the antifascists of St. Petersburg decided to stop "Russian March". About 50 people blocked Nevsky Prospekt, where a unit of several hundred nationalists was proceeding. (They had around 50 "fighters" as well, Katya says, the rest of them — deranged grandmas and other gonfaloniers.) There was no police to be seen — even though the city government hadn't authorized the procession — right until the moment when the antifascists appeared. When they blocked Nevsky Prospekt the police tried to stand between them and the marchers, then Katya heard a command from a police walkie talkie saying "Give them a corridor!" and the police stepped aside, but Katya was attacked by one of the marchers, who yelled "Punch the Jews!" for some reason. He received a kick to the stomach from her, stepped back, but then Katya got jumped from behind by the OMON [translator's note: Special Purpose Police Unit], and with the words "Grab this one!" they dragged her into a bus.

Then there was a trial. "Either for jaywalking, or for insulting the governor," Katya laughs. The fight was not mentioned in the criminal case: "They didn't want to draw attention to those we came out against". But the judge turned out to be so attentive and curious that Katya herself told everything in detail at the court hearing. The result was unexpected. "What? You were fighting fascists?!" the judge asked with respect. "My parents are survivors of Leningrad Siege, I understand you so well!" And that's how Katya got cleared of all charges.

I am talking with her in the park near Polytechnic University. The place is next to Muzhestva Square [translator's note: Square of Courage]. Katya tells me how the square got its name: during the siege corpses from all over the city were brought here before being buried at Piskaryovka. "The fash are fash everywhere, but in a city like this, of course, it's especially unpleasant to see them," Katya says.

As we walk to the metro station through another park near the Forestry Academy, Katya tells me that one time her neighbour, a well-mannered elderly woman, took this same road one evening and saw two guys with characteristic skinhead appearance following an African student. The woman didn't flinch and jumped at them with her purse shouting "Get lost, fascists!" And they obeyed. "So it's hard to tell how many antifascists there are in the city that are prepared to take direct action," Katya laughs. "But there are about a hundred of those who do it constantly."

She totally approves of the actions of Rash and his friends. I tell her about Maxim Ivantsov, his worries, and tolerance trainings.

"You know, I don't like the word "tolerance"," Katya says harshly. "There are things you shouldn't tolerate. I myself despise fascism with fierce animalistic hatred. I'm not a tolerant person."

There is also a more pragmatic point of view.

"Cynically speaking, as long as bons are distracted by us, they will slaughter fewer Tajiks or Uzbeks," says another older comrade of Rash, also a former member of "Punk-vozrozhdenie" [translator's note: "Punk-revival"], Zhenya with the nickname Slon [translator's note: Elephant], as he answers my question about the efficiency of antifascist street violence.

"Is that enough?"

"It's not enough, but it's important. That's why it shouldn't be said that violence from our side is not justified."

Zhenya tells me about a recent article in some Russian publication about left radicals in Germany who thrashed Hamburg earlier this year on March 1st under antifascist slogans, attacking policemen and burning cars — in which the author of the article reasons that antifascists are no different from fascists in their methods. As a result, the author even calls them "followers of their loathed Hitler".

Zhenya, of course, was infuriated by the article. Contemplating nazi violence, he references another text, from an antifascist website, the author of which draws parallels between the current burst of nazi violence in Russia and the terror in Ulster, Ireland in the 1970s - 1980s, when The Shankill Butchers (a gang of militant Protestants) slaughtered, tortured, and murdered random Catholics with silent approval from peaceful Protestants. "The movement of Moscow boneheads follows the same scenario. The only difference is that the bons who do the murders are younger. If there are people predisposed to this, and if the society they are in justifies such behaviour, they will very quickly become dependent on violence," the author writes.

I asked Zhenya to send me links to both articles, read through them, and was surprised. The two texts he referenced to illustrate two opposite points of view essentially turned out to be about the same thing. They talk about how violence that doesn't meet any resistance in its own environment — be it the Irish Protestants, the Russian boneheads, or the German antifascists, — inevitably becomes uncontrollable, easily crossing the line between the necessary self-defence and attacking for the sake of attacking.

Grandmother

This May, Leninsky City District Сourt of St. Petersburg delivered a verdict on a case of a mass fight with several dozens of people on both sides. In September of 2006 the Movement Against Illegal Immigration (DPNI) supporters held a rally on Pionerskaya Square due to the events in Kondopoga, Republic of Karelia. They had barely managed to set up when they got attacked by approximately 30 antifascists with flares and bottles. This was the largest "combat" action of St. Petersburg antifa in the entire history of the movement. Around twenty people were arrested, six of them went on trial for hooliganism as a result — including Rash who was charged with organisation of the fight and involvement of minors in criminal acts. The prosecutor demanded a six year jail sentence for him.

Rash wasn't even arrested at the place of the fight — or, to be more precise, he was, but got instantly released from the police station after giving a policeman three thousand rubles [translator's note: ~112 USD, according to the official September 2006 exchange rate]. He only became an indictee later, based on the testimonies of other detainees. He says that he didn't organise the fight, that nobody was organising it at all: "There was an antifascist concert in a club the night before, and somebody said that the next day nazis were gathering for a rally, so why not go fuck them up. Well, we decided on the time and showed up."

Rash was left with a mixed impression on the court hearing. On the one hand, DPNI have pleasantly surprised him:

"They turned out to be complete dumbasses — babbled such nonsense at the hearing! The judge asks them: how did you end up at the crime scene? They had so much time to come up with anything, they all had lawyers, wouldn't even testify without their presence. But they were mumbling stuff like "happened to be passing by, suddenly a bottle hit me in the head". Frankly speaking, I expected them to be smarter and more dangerous. But they just parrot people's kitchen talk from the tribunes — about "the dominant influence of blacks" and all that stuff, and don't have any meaningful organisation behind that."

On the other hand, these "dumbass" opponents put a lot of effort into sending Rash to jail. And he didn't really believe he could avoid it at that point.

The verdict was announced on May 8th, the day before Victory Day, and, perhaps, that's why it was milder than what the prosecutor and the victims were hoping for. Rash was sentenced to a year of probation period, the other indictees — even less than that. Rash's attorney at the hearing was Zara Kaloeva, for whom defending him became her first criminal case in 47 years of legal practice. Rash is her grandson.

The grandmother explained to the investigation officer who initially wanted to arrest Rash that the fight was not an act of hooliganism, but a political act. She kept repeating the same in court, adding that fascism must be fought not by individuals in the streets, but by the State. She forbade Rash to give any testimony so that the prosecutor wouldn't have anything to catch him on. Enthusiastically heard out the information prepared and recited in court by some research center about who antifascists are in Russia: if she understood correctly, they are "diffuse groups".

The life of her own grandson is not much easier to picture. However, she told the story of Rash dropping out of university in much more detail than Rash himself did. Saint Petersburg State Institute of Culture wasn't his first academic institution, he previously studied Chinese at the Polytechnic University. Finished two years, for the third one he had to go to China for practice. From his own pocket. Rash's mother is a teacher, his father died several years ago. His grandmother was prepared to cover it, but he refused. And he didn't go. Either so that she wouldn't have to pay, or because he had more important business in St. Petersburg than the Chinese language. So he had to look for another school. And that's how he ended up on the Faculty of Sociology. Got to the fifth year, with only the last set of winter exams and his final thesis left. But in autumn he attacked the DPNI rally and the investigation officer promised him that he will go to jail, so he stopped showing up at the university. And that's how he got expelled — on his final year. However, it doesn't seem like Rash has any strong regrets. "I know one fellow sociologist who graduated with honors — now works at a parking lot," he told me.

I asked Zara Vladimirovna where people like Rash even come from, but it seemed like she was confused herself.

"Neither me, nor my daughter have ever told him anything like that. He told me once though that it was his father who taught him to 'love the Motherland', as he put it. Well, he also reads books. Classic literature. And anarchists. He once told me about anarchy: 'Everybody thinks anarchy is disorder, but it's actually the best order really!' He also once said: 'I don't understand how you can watch everything happen and do nothing'."

Concert

At the children's club "Lyzhnik" [translator's note: "Skier"] owned by the factory of the same name in Kirov, an antifascist gig is taking place: several local hardcore and punk bands and a guest band Crowd Control from St. Petersburg, where Rash plays. Similar events are being organised by local antifascists every month. Previously, they say, it used to happen more frequently. Several years ago Kirov was even considered the Russian capital of antifascism: there almost were fewer bons than antifa there. Nowadays, many antifascists are under parole, which makes them act with caution. That's why now there are more bons again.

Above the tiny children's stage of "Lyzhnik" there is a garland reading "Farewell, primary school!", on the opposite wall — an "Anti-Fascist Action" banner and a poster for a gig called "Rise Up, Shit!". During the intermissions between band performances, the entire hundred, if not more, of spectators scatters out into the street to occupy the colourful kids' benches, and Kirov's law abiding passersby quicken their pace when they see this riot of mohawks, tattoos, and hoods.

"We want to dedicate this next song to the memory of our granddads who fought fascism," the frontman of a band playing before Crowd Control says from the stage.

He sings: "They fought against fascism, they only went forward and didn't know there would be new deaths in a new fascist war." I look at the faces around me. The faces look normal, if you ignore the mohawks. All sober, by the way, — about three drunk people at most. There's also a couple of gopnik-looking ones, but everyone else has calm eyes and nice faces. All of them standing there, listening about granddads.

Crowd Control take the stage. Rash is on guitar, the vocalist is that sociologist who graduated with honors. Rash's brother, one year older than him, also plays in the band. This Kirov show is a part of the tour to support their new album, before Kirov they did shows in Moscow and Nizhny Novgorod. The band members have covered all that distance as a group of five in one car — couldn't afford even the cheapest train tickets. The album can be bought right here for 50 rubles. "All proceeds will go to our comrades from the St. Petersburg organization Anarchist Black Cross," Rash says from the stage. "As in, you donate 50 rubles to this organisation and get our album as a gift."

They start playing. I can't make out the lyrics — it's hardcore after all. Looking at the vocalist's face twisted with inner energy one can imagine anything but his Sociology degree. "Fucking great!" the audience yells in approval.

Each song is preceded by an introduction.

"This next work is called "Hell on Earth", and it is dedicated to the ecology topic, which we consider very important, especially for our Leningrad Oblast. And very recently, as you might have heard, an emission of harmful substances happened at a nuclear plant near St. Petersburg, and even though the government and other "greenpeaces" are assuring us that in reality nothing happened — we still know the truth," Rash says.

There actually was no explosion at LAES [translator's note: Leningrad Nuclear Power Plant] after all — that was a false alarm, but Rash either really doesn't believe that, or rightfully assumes that 16 — the average age of the listeners in the hall — is not a time when one is interested in details.

After the government and "Greenpeace", they take shots at mass media (the song is titled "Hysteria"), then the Church (Rash is certain that religion is a method of manipulating the mass consciousness), then also the lovers of meat and fur. "I call upon you all to become vegetarian. They've stuffed your head with bullshit like how you can't do bodybuilding if you don't eat meat, but in reality dairy protein gets digested better. It is also fucking shitty to wear fur and leather," Rash explains from the stage. Then he proceeds to the main point:

"We want to say that antifascists shouldn't stop at just fucking bons up. Fascism exists not only in the streets, but in the kitchens, in the parliament. We must change the public consciousness. When they stop talking in kitchens about "blacks overrunning the country", bons will disappear from the streets on their own."

The concert ends, and the organisers ask that nobody leaves on their own — everyone must go together, otherwise it's dangerous: almost all gig posters got torn down by local nazis, they know about the event and can attack. But as a united crowd of a hundred people we safely reach the bus stop and pack ourselves into two buses. Only the fare collector seems to be scared. The buses go to "kvadrat" [translator's note: "square"] — a hangout spot for local punks and antifa. There, an after-party will take place: beer, discussions, and, with any luck, a brawl with bons.

Rash has changed out of the concert t-shirt into a hoodie with "Nazi Hunter" printed on it — a nazi hunter, now with a crowbar instead of a guitar in his hands. But thanks to his smile, even looking like that he doesn't seem threatening. I ask if he's afraid that antifascist violence will become as uncontrollable as the fascist one, and that his brothers-in-arms will become indistinguishable from bons apart from slogans.

"Well, yeah, such danger exists," he says. "But we try to explain that our goal is not killing fascists, but making them realise that they are not safe, that what they do is bad and will be punished. Especially when it's not some murderers, but youngsters who simply put bombers on and "hunt blacks" out of stupidity. Most of all, I'm afraid that these youngsters will start getting killed. But I always tell our guys to not fight mindlessly: always think before you attack, evaluate who's in front of you. Our goal is not punching another bonehead in the face, but stopping the violence coming from their side."

Rash is interesting company. He's somehow very real, without a hint of showing off, despite his age and circumstances. What is even more surprising, there's no aggression in him — neither in his words, nor the eyes, nor his mannerisms. Charming, almost a happy-go-lucky guy. Should have just continued studying Sociology, dammit!..

"What," I ask, "are you going to do in about ten years?"

"In ten years?" he shrugs. "I think by that time I'll either be in jail, or killed."

Saint Petersburg — Kirov

Photos: Yulia Lisnyak for "RR".

#book club #antifa #russia #2000s #translation #cohost repost

Comments